Impact of Oral Health on Overall Health Peer Reviewed

- Research article

- Open up Admission

- Published:

Impact of oral health on health-related quality of life: a cross-sectional study

BMC Oral Health volume 16, Article number:55 (2016) Cite this article

Abstract

Background

Despite the consensus regarding the being of a relationship betwixt "impacts on oral health" and "health-related quality of life", this human relationship, considering the latent nature of these variables, is still poorly investigated. Thus, we performed this written report in club to determine the magnitude of the impacts of oral wellness, demographic and symptom/clinical variables on the health-related quality of life in a Brazilian sample of dental patients.

Methods

A total of 1,007 developed subjects enrolled in the School of Dentistry of São Paulo Country University (UNESP) - Araraquara Campus for dentistry care between September/2012 and April/2013, participated. 72.4 % were female. The hateful age was 45.seven (SD = 12.five) years. The Oral Health Bear on Profile (OHIP-xiv) and the Brusk Grade Wellness Survey (SF-36) were used. The demographic and symptom/clinical variables nerveless were gender, historic period, economic status, presence of pain and chronic disease. The impact of studied variables on wellness-related quality of life were evaluated with a structural equation model, because the factor "Health" as the primal construct. The fit of the model was first analyzed past the evaluation of the goodness of fit indices (χtwo/df ≤ two.0, CFI and TLI ≥ 0.90 and RMSEA < 0.x) and the evaluation of the variables' impact over health-related quality of life was based on the statistical significance of causal paths (β), evaluated by z tests, for a significance level of 5 %.

Results

We observed adequate fit of the model to the information (χ2/df = 3.55; CFI = 0.95; TLI = 0.94; RMSEA = 0.05). The impacts on oral wellness explained 28.0 % of the variability of the health-related quality of life construct, while the full variance explained of the model was 39.0 %. For the demographic and symptom/clinical variables, but age, presence of pain and chronic disease showed pregnant impacts (p < 0.05).

Conclusion

The oral health, historic period, presence of pain and chronic disease of individuals had pregnant influence on health-related quality of life.

Background

The health-related quality of life is a complex and multidimensional construct composed of a gear up of concepts. The first articles that fabricated reference to the term "health-related quality of life" were published in the mid-1980s and since and then, many changes have been attributed to this definition and measurement [ane]. According to Dijkers [2], wellness-related quality of life is an important component of quality of life, being composed by physical, cognitive, emotional and social aspects. Nowadays, it is well known that it can be modulated directly or indirectly by imbalances in wellness every bit diseases, disorders or injuries, being sensitive to the signs, symptoms and treatment effects [three]. Thus, this construct tin be assessed both by general or by specific approaches, such as oral health [4].

In the literature, there are several theoretical approaches and conceptual frameworks proposed to assess the Health and the Oral health-related quality of life [4–nine]. Individual perceptions regarding the oral wellness impact contour have been growing in importance since they can influence the cocky-care practices and tin can take a direct effect on health-related quality of life of individuals.

One of the nigh widely used instrument to assess the "impact on the oral health" is the Oral Health Impact Contour (OHIP) proposed by Slade and Spencer [8] based on the model proposed by Locker [10]. The OHIP evaluates three conceptual domains (concrete, psychological and social) that quantify the private perception of the impacts generated by oral problems in general health.

The wellness-related quality of life, in turn, has been evaluated past estimating the touch on of symptoms, disabilities or limitations that may consequence in disturbance of individual well-being [11]. The Short Class Health Survey (SF-36) is a generic health indicator most commonly used for this purpose [11]. The SF-36 consists of two conceptual domains "physical health" and "mental health", which converge to the individual perception of "health", and the estimation of wellness-related quality of life of individuals. In this instrument eight health concepts were measured, selected from dozens included in the Medical Outcomes Study model [12].

According to Locker studies [7] oral health tin can affects people physically and psychologically and tin can influence many aspects as how they savour life, speak, chew, taste food, socialize and the social well-being. Thus, some contempo studies in the scientific literature evaluated the impact of general [13] and specific aspects of oral wellness, as the use of prostheses [fourteen], surgical treatments [15], parafunctional habits [sixteen], dental pain [17], among others, on quality of life in different samples, being common the association of oral conditions evaluated on the factors of health-related quality of life of patients.

Despite the consensus regarding the existence of a relationship betwixt "impacts on oral wellness" and "health-related quality of life" [vii] and the development of some models to evaluate these constructs [eighteen, 19], this relationship, because the latent and multidimensional nature of variables, is still poorly investigated. As far as nosotros know, only the study of Reissman et al. [18] aimed at evaluating the contribution of oral health impacts, demographic and symptom/clinical variables on health-related quality of life, preserving the latent nature of these variables. However, the theoretical model presented by these authors considers both the wellness-related quality of life and the oral health bear upon profile as dependent variables and estimates the relationship between them through correlational assay.

Some other aspect to be considered is that, through the cess of the touch of oral issues on health-related quality of life, we can make a vital contribution to improve the prevention and dental intervention strategies, promoting a better quality of life for individuals.

Thus, we performed this study in society to determine the magnitude of the impacts of oral health, demographic and clinical variables on the health-related quality of life in a Brazilian sample of dental patients.

Methods

Study design and sampling

A cross-sectional written report with non-probabilistic sampling design was developed.

The estimation of the sample size was performed considering the proposal of Hair et al. [20]. According to this author, the sample size necessary was estimated considering the need from vii to ten subjects per parameter to be estimated in the model. (final model' parameters: OHIP: n = 34, SF-36: north = 77, demographic and symptom/clinical variables: n = 5). Thus, we obtained an gauge of the sample size of 812 to 1,160 subjects [xx]. Assuming a loss charge per unit of 15 %, the minimum sample size required for structural equation modelling was estimated at 956 to 1,365 subjects.

A total of 1,925 adult patients, who sought dental intendance in the School of Dentistry of São Paulo State University (UNESP), Araraquara Campus from September of 2012 to April of 2013 were invited to participate. Of these, ane,203 agreed to participate (adhesion rate = 62.v %). Simply those participants who completed all items of the demographic questionnaire and measuring instruments (SF-36 and OHIP-14) were included, resulting in a last sample size of 1,007 patients.

Written report variables

The study variables were gender, historic period, economic class, presence of hurting at the fourth dimension of questionnaire awarding (yes or no) and presence of chronic affliction (yep or no). The selection of these variables were based in previous studies and models of oral and general health assessment [18, 21–23]. To identify patients with pain, all the participants responded the question "Are you in pain at this moment?" If aye, they indicated the location. It should exist clarified that it was not carried out any clinical examination to verify the presence or absence of hurting, i.e., for this report was considered only the referred hurting. The economic classes were classified co-ordinate to the Brazilian Economic Classification Criterion - ABEP [24]. To narrate the sample, other data were collected like the type of chronic affliction and the dental condition (dentate, edentulous or fractional edentulous), employ of dental prosthesis (yes or no) and the type (fixed partial denture, removable partial denture or complete denture).

Measuring musical instrument

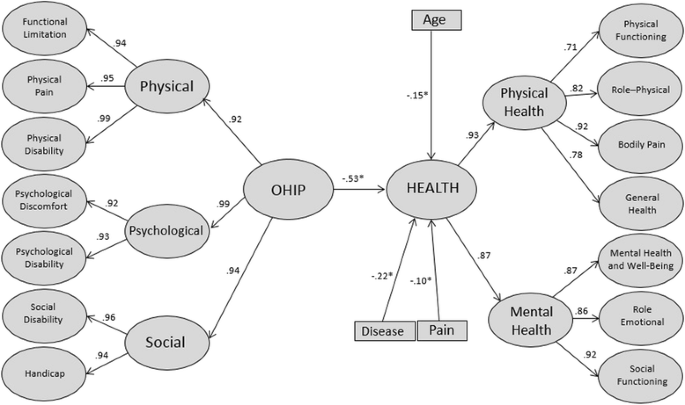

The oral health impact profile was estimated using the Portuguese reduced version of the Oral Health Impact Contour (OHIP-14) proposed by Oliveira and Nadanovsky [25]. This version of the musical instrument is composed by 14 items bundled in seven first-order factors (functional limitation, physical pain, psychological discomfort, concrete disability, psychological disability, social disability and handicap). The answers are given in a five-bespeak type Likert scale (0 = never, 1 = rarely, 2 = sometimes, 3 = often, four = always). Zucoloto et al. [26] evaluated the psychometric backdrop of this instrument in the sample of this study and they attested the validity and reliability of the OHIP-xiv. They proposed a third-club hierarchical model composed by the second-social club factors "Physical", "Psychological" and "Social" and one third-order factor called "OHIP". The fit of third-order hierarchical model was adequate (λ = 0.62-0.83, χii/df = vii.67, CFI = 0.94, GFI = 0.93 and RMSEA = 0.08; Cronbach's alpha = 0.62-0.77; Blended Reliability = 0.63-0.77) and this was the model used in this written report.

The Health-related quality of life was estimated using the Portuguese version of the Curt Form Health Survey (SF-36), in the standard format (remember period of 4 weeks), provided by Quality-Metric Incorporation® (Copyright: QM13691). The factorial structure used was composed of seven first-club factors (physical functioning, role-physical, bodily hurting, general health, social functioning, part-emotional and mental wellness and well-being), two 2d-society factors (Physical Health and Mental Health) and a third-social club gene (Wellness), whose psychometric backdrop accept been attested in a previous written report for the sample of this study (λ = 0.46–0.ninety, χ2/df = 5.90, CFI = 0.90, TLI = 0.ninety and RMSEA = 0.06; Cronbach's blastoff = 0.76–0.93; Composite Reliability = 0.70–0.94) [27]. The answers are given in a type Likert scale of three point for the gene "Concrete functioning" and five points for the other factors.

Procedures

The questionnaires were self-completed in the waiting room of the clinics of the School of Dentistry of São Paulo State University (UNESP) (general clinic and specialties clinics such as prosthesis, endodontics, surgery and periodontics), earlier the dental process. Patients who had difficulty in filling the questionnaires were interviewed (16.eight %). The questionnaires were presented in random order to minimize the bias in the fill. Merely individuals anile xviii years or more than participated.

Statistical Analysis

Structural Model

A structural equation model was congenital considering the demographic, symptom/clinical and OHIP variables' impact on the third order hierarchical cistron "Health", estimated by the SF-36, (dependent variable). The variables "oral health touch profile", age, gender, economical class, presence of pain and chronic disease were considered, in the model, as predictors variables. The goodness of fit of this causal model was evaluated on the polychoric correlation matrix using Weighed Least Squares Mean and Variance Adjusted (WLSMV) estimation, as implemented in the software MPLUS 6.0 (Muthén & Muthén, Los Angeles, CA). The fit of the model was start analyzed by the indices of goodness of fit and was considered adequate if χtwo/df ≤ 2.0, CFI east TLI ≥ 0.90 and RMSEA < 0.ten [28]. The significance of the predictor variables on the Health central construct was judged form the statistical significance of the paths (β), assessed past z tests, for a significance level of 5 % [28].

Ethical aspects

This study was authorized past the Research Ethics Committee of the Kinesthesia of Dentistry of Araraquara - UNESP (CAAE: 01040312.5.0000.5416-n° 50802). The study included only individuals over xviii years of age who agreed and signed the Gratis and Informed Consent Class. Authorizations for the utilise of the instruments were acquired together with the authors (OHIP-14) and competent agencies (SF-36 Quality Metric Inc. - License: QM13691).

Results

The mean age of the participants was 45.7 (SD = 12.5) years and 72.4 % were female.

Table 1 shows the distribution of the patients according to demographic and symptom/clinical characteristics.

The sample consisted generally by partial edentulous subjects with low economical condition. Of participants who reported the presence of pain (n = 358), 61.2 % had a toothache, 17,iii % a face up hurting, 9,8 % a head pain, vii,8 % a pain in the ear region/temporomandibular joint and 3,nine % in other orofacial region. The about prevalent chronic diseases were hypertension (25.three %) and diabetes mellitus (20.2 %).

The structural model equanimous by all independente variables presented adequate fit to the sample (χ2/df = 3.55; CFI = 0.95; TLI = 0.94; RMSEA = 0.05-Explained variance of the model: 39.0 %). OHIP has negative and significant impact over wellness-related quality of life (β = −0,53; p < 0,05). The higher the touch on oral health, the lower is the health-related quality of life. This path explains 28.0 % for the variability of primal construct. Regarding demographic and symptom/clinical variables, the age, the pain and the presence of chronic disease showed negative and meaning trajectories (p < 0,05), although they presented low contribution to the explanation of the central construct, being three.6, i.2 and 4.four %, respectively. At that place was no significant contribution (p > 0.05) of gender or economical class to health-related quality of life.

Subsequently, a refined model (including merely pregnant variables) was analysed. The refined model too presented an adequate fit to the information (β = −0.53 to −0.x, χ2/df = 4.27, CFI = 0.93, TLI = 0.93, RMSEA = 0.06) (Fig. 1). The explained variance of the refined model was 36.ane % and the contribution of the OHIP to the primal construct continued on 28.0 %.

Structural refined model for assessment the contribution of the impact of oral wellness (OHIP), demographic and symptom/clinical variables on Health-related Quality of Life (Health). Araraquara, São Paulo, Brazil, 2013

Word

The results presented in this study show a pregnant contribution of the touch on of oral health on health-related quality of life, suggesting to farther consider this construct in wellness-related quality of life research [4, vii].

In this present study, we introduce a singled-out theoretical proposal, aiming at estimating the contribution of the touch of oral health on wellness-related quality of life. This proposal preserves the latent feature of the variables (OHIP-14 and SF-36) and the functional human relationship of each to the construction of the concepts, ie, the oral health impact profile were considered the independent variable and the health-related quality of life the dependent variable. Thus, we presented a possibility of develop a predictive model that goes beyond correlational patterns betwixt the variables.

Information technology is worth mentioning that is not possible to straight compare our results with previous published enquiry, because there is a lack of studies that preserve the latent characteristics of the constructs assessed. The theoretical model presented is different of others previously tested in the scientific inquiry.

Some other noteworthy aspect is that, despite the widespread utilize of the SF-36 and OHIP-14 in the literature, few studies investigated the psychometric backdrop of the instruments prior to use in their study samples [5, 29]. This step was presented in this study and it is essential to provide evidence regarding the quality (validity and reliability) of the obtained data [28, 30, 31].

In the predictive model proposed (Fig. 1), it tin be observed a significant changed human relationship of the impacts of oral wellness on health-related quality of life. This relationship accounts for 28.0 % of the variability of the central construct, which tin can be considered an of import contribution, in view of the complexity and multidimensionality of the health-related quality of life. This fact signals to the importance of oral wellness to general health of individuals. Therefore, our results emphasize the importance of the oral health, which should demand special attention by health professionals [7]. It is noteworthy, all the same, that the important explained variance detected in the structural model evaluated can exist related to the characteristics of the sample. The study included only patients who sought dental care, it ways, they have some harm/dissatisfaction with their oral health. Dental patients potentially take worst dental clinical status, more perceived dental handling need and more impact of oral health on general health. Thus, farther studies should test this model to be tested in populations without oral issues to verify the contribution from the bear upon caused by oral problems in these persons.

Among the demographic variables included in the model, but historic period was a significant predictor (Fig. 1), i.e., the health-related quality of life is worse with increasing age. Similar results were found in published research. This results can exist justified by greater touch of oral and systemic diseases in elderly individuals [19, 32–35].

Regarding symptom/clinical variables, the presence of "chronic affliction" and "pain" showed meaning contributions to the health-related quality of life. Importantly, the presence of hurting and chronic disease have been considered essential variables in studies of health-related quality of life and oral health-related quality of life due to impacts on the wellbeing of individuals [7, 36].

A limitation of this study may be the not-probabilistic sampling blueprint adopted. However, this strategy has been commonly utilized in validation studies. The utilise of sufficient sample size ensures credibility of the decision-making that results from the statistical tests. Another limitation is the use of self-referred information about dental condition and use/type of dental prosthesis which express their inclusion in the predictive model. This type of data collection strategy was used due to the big sample size. However, information technology is suggested the fulfillment of studies that include oral clinical examination as a methodological strategy in order to verify the possible contribution of these variables to the model presented.

With this written report, nosotros provide relevant information to healthcare professionals, on the impacts caused by oral problems in wellness-related quality of life. This knowledge can guide the evolution of preventive strategies and more resolute and all-encompassing treatments focusing non only in solving oral problems, merely also considering their bear on on the overall health of individuals.

Conclusion

The variables "oral health impact profile", historic period, chronic disease and presence of hurting showed pregnant influences on wellness-related quality of life.

Abbreviations

- CFI:

-

comparative fit index

- OHIP:

-

oral wellness affect profile

- OHIP-14:

-

oral wellness impact profile-short form

- RMSEA:

-

root hateful square error of approximation

- SF-36:

-

short form health survey

- TLI:

-

Tucker-Lewis index

- WLSMV:

-

weighed to the lowest degree squares hateful and variance adjusted

- β:

-

regression coefficient

- χ2/df:

-

ratio of chi-square by the degrees of liberty

References

-

Mail service MWM. Definitions of Quality of Life: What Has Happened and How to Move On. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil. 2014;20(iii):167–80.

-

Dijkers M. "What's in a name?" The indiscriminate use of the "quality of life" label, and the need to bring about clarity in conceptualizations. Int J Nurs Stud. 2007;44(one):153–five.

-

Dijkers M. Quality of life later on spinal cord injury: A meta analysis of the effects of disablement components. Spinal Cord. 1997;35(12):829–twoscore.

-

Slade GD. Oral health-related quality of life is of import for patients, only what about populations? Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2012;40(2):39–43.

-

Keller SD, Ware Jr JE, Bentler PM, Aaronson NK, Alonso J, Apolone Chiliad, Bjorner JB, Brazier J, Bullinger Chiliad, Kaasa S, et al. Use of Structural Equation Modeling to Exam the Construct Validity of the SF-36 Healthy Survey in Ten Countries: Results from the IQOLA Projection. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51(11):1179–88.

-

Slade GD. Derivation and validation of a short-course oral health bear on profile. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1997;25(iv):284–xc.

-

Locker D. Concepts of oral wellness, disease and the quality of life. In: Measuring oral health and quality of life. Chapel Hill: Academy of North Carolina; 1997.

-

Slade GD, Spencer AJ. Development and evaluation of oral health impact profile. Customs Dent Health. 1994;11(1):3–11.

-

Thomson WM, Mejia GC, Broadbent JM, Poulton R. Construct Validity of Locker's Global Oral Health Item. J Dent Res. 2012;ix(11):1038–42.

-

Locker D. Measuring oral health: a conceptual framework. Community Dent Health. 1988;five(one):iii–18.

-

McHorney CA, Ware JEJ, Raczek AE. The MOS 36-Item Short Grade Health Survey (SF-36): 2. Psychometric and clinical tests of validity in measuring physical and mental wellness constructs. Med Intendance. 1993;31(3):247–63.

-

Ware JE, Gandek B. Overview of the SF-36 Wellness Survey and the international quality of life assessment (IQOLA) Project. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51(xi):903–12.

-

Leão MM, Garbin CA, Moimaz SA, Rovida TA. Oral health and quality of life: an epidemiological survey of adolescents from settlement in Pontal do Paranapanema/SP. Brazil Cien Saude Colet. 2015;xx(xi):3365–74.

-

Cano-Gutiérrez C, Boorda MG, Arciniegas AJ, Borda CX. Edentulism and dental prostheses in the elderly: impact on quality of life measured with EuroQol - visual analog scale (EQ-VAS). Acta Odontol Latinoam. 2015;28(two):149–55.

-

Mustafa AA, Raad M, Mustafa NS. Effect of proper oral rehabilitation on general health of mandibulectomy patients. Clin Case Rep. 2015;three(xi):907–11.

-

Carvalho AM, Lima Medico, Silva JM, Neta NB, Moura LF. Bruxism and quality of life in schoolchildren aged 11 to 14. Cien Saude Colet. 2015;xx(11):3385–93.

-

Yang SE, Park YG, Han Chiliad, Min JA, Kim SY. Dental hurting related to quality of life and mental health in Southward Korean adults. Psychol Health Med. 2015;10(1):i–12.

-

Reissman DR, Jhon MT, Schierz O, Kriston 50, Hinz A. Association between perceived oral and general wellness. J Dent. 2013;41(7):581–9.

-

Zimmer Southward, Bergmann Northward, Gabrun East, Barthel C, Raab W, Rëffer JU. Association betwixt oral health-related and general health-related quality of life in subjects attending dental offices in Frg. J Public Wellness Dent. 2010;lxx(2):167–seventy.

-

Hair JF, Blackness WC, Babin B, Anderson RE, Tatham RL. Multivariate data assay, 6th edn: Prentice Hall. 2005.

-

Sabbah West, Tsakos G, Chandola T, Sheiham A, Watt RG. Social gradients on Oral and Full general Health. J Paring Res. 2007;86(ten):992–6.

-

Hays RD, Revicki D, Coyne KS. Application of structural equation modeling to wellness outcomes enquiry. Eval Wellness Prof. 2005;28(3):295–309.

-

Lam WYH, McGrath CPJ, Botelho MG. Impact of complications of unmarried tooth restorations on oral wellness-related quality of life. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2013;0:ane–7.

-

Associação Brasileira de Empresas de Pesquisa. Critério de Classificação Econômica Brasil - 2011 abep.org/codigosguias/Critério_Brasil_2008.pdf

-

Oliveira B, Nadanovsky P. Psychometric properties of the Brazilian version of the Oral Health Touch Profile - short form. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2005;33(4):307–14.

-

Zucoloto ML, Maroco J, Campos JADB. Psychometric backdrop of the oral health bear on contour and new methodological aproach. J Paring Res. 2014;93(7):645–50.

-

Zucoloto ML, Maroco J, Campos JADB: Psychometric Properties of the Short Course Health Survey (SF-36) in a Brazilian sample: Validation study. BMC Wellness Services 2015, in press.

-

Maroco J. Análise de Equações Estruturais. 2nd ed. ReportNumber: Lisboa; 2014.

-

Bakery SR. Testing a Conceptual Model of Oral-Wellness: a Structural Equation Modeling Approach. J Dent Res. 2007;86(8):708–12.

-

Anastasi A. Psychological testing. sixth ed. New York: Macmillan Publishing Company; 1988.

-

Borsboom D, Mellenbergh GJ, Heerden J. The concept of validity. Psychol Rev. 2004;111(4):1061–71.

-

Ulinski KGB, Nascimento MA, Lima AMC, Benetti AR, Poli-Frederico RC, Fernandes KBP, Fracasso MLC, Maciel SM. Factors related to oral wellness-related quality of life of contained Brazilian elderly. Int J Dent. 2013;2013:1–18.

-

Baker SR, Pearson N, Robinson PG. Testing the applicability of a conceptual model of oral health in housebound edentulous older people. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2008;36:237–48.

-

Locker D, Slade GD. Association between clinical and subjective indicators of oral health status in a older adult population. Gerodonthology. 1994;11(ii):108–14.

-

Peek K, Ray L, Patel K, Stoebner D, Ottenbacher KJ. Reliability and Validity of the SF-36 amidst Older Mexican Americans. Gerodontologist. 2004;44(three):418–25.

-

Segù Thou, Collesano 5, Lobbia Due south, Rezzani C. Cantankerous-cultural validation of a short course of the Oral Health Touch on Contour for temporomandibular disorders. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2005;33:125–30.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank São Paulo Enquiry Foundation (FAPESP) for financing this written report (Procedure: 2012/01590-3 2012/01856-3).

Author data

Affiliations

Corresponding author

Boosted information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they accept no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

MLZ became involved with data drove, statistical analysis and drafting the first version of the manuscript. JM gave substantial contributions to formulation, pattern and strategies for information analysis. JADBC was involved in the development of the chief thought for the manuscript and she has given terminal approval of the version to be published. All authors read and approved the terminal manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Admission This article is distributed nether the terms of the Artistic Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/four.0/), which permits unrestricted apply, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided y'all give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Artistic Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Eatables Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/cipher/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zucoloto, Yard.Fifty., Maroco, J. & Campos, J.A.D.B. Impact of oral health on health-related quality of life: a cross-exclusive written report. BMC Oral Wellness 16, 55 (2016). https://doi.org/ten.1186/s12903-016-0211-2

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-016-0211-2

Keywords

- Oral health

- Full general wellness

- Quality of life

- Oral wellness surveys

Source: https://bmcoralhealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12903-016-0211-2

0 Response to "Impact of Oral Health on Overall Health Peer Reviewed"

Post a Comment